“AGENCY: ON WHO’S TERMS”

“AGENCY: ON WHO’S TERMS”

Curated by Collaborated with Clayton Windatt

Curatorial statement by Clayton Windatt: It has become an ongoing thematic within my work as an activist and within advocacy circles within the art sphere to challenge who has the right to dictate terms. As a Métis (mixed blood) individual that benefits from being publicly presented often as a white male, I must ensure that my privilege is checked consistently and that all actions come from a place of mutual benefit to self and those I am trying to serve. I often work hard to find ways to take up less space while ensuring my own survival, passing benefit to those around me and attempting not to take credit for drawing attention to those amazing people beside me. I work as the Executive Director of the one of the few Indigenous-specific Arts Service Organizations in North America and my role often puts me in the position of having to speak on behalf of many people. Sometimes my role is to speak on behalf of all Indigenous people in the world and the only comment I make when asked to do this is; “I can only speak with my own voice”. In a world where many peoples are seeking ways for higher levels of cultural pluralism and representation, “self” becomes something hypothetical and reminders must be made. I never speak on behalf of others unless they explicitly ask me to and are prepared to stand with me for our shared message.

The term “curator” is also a concept that’s current relevance I challenge as the term makes me feel sick. A “curator” from the Latin “curare” which means, “to take care” as a manager or overseer. A large majority of the public today envisions the term “curator” as a keeper of a cultural heritage institution such as a gallery, museum, library, or archive. I am none of these things nor would I ever want to be. Becoming the Overseer of a place where cultural heritage is preserved sounds like the worst thing I could do to myself. It sounds like being the Warden of a maximum-security cultural prison where the objects found within all have death sentences. I understand that many Museums around the world are making effort to change the way they are perceived and activate their collections to avoid this exact opinion but I cannot stop myself from being fundamentally opposed to their existence as culture needs to be expressive and free of rigid colonial constraints.

Within film; I am called a programmer, within theatre; I am called an artistic director, within visual art; I am called a curator. All these roles mean the same thing to me; the rally point for the project, the person responsible influencing creative decisions but what happens when the creative decisions are to ask others for their input, their direction or facilitating a platform for their own messages to be heard? Is this still curatorial practice? Not in a conventional sense and not in my practice. I do not identify as a conventional curator; I am an artist, coordinator, facilitator, advocate and a person prepared to transfer power whenever possible. I allow people to apply the term curator to me as it helps them to understand a role but for the artists I work with, I hope the conventional label of curator never crosses their minds.

It is this philosophy that I bring to projects. I challenge and stand beside people. I am not a content specialist charged with an institution’s collections or involved with the interpretation of heritage material. As a traditional curator’s focus involves tangible objects of artwork, collections, historic items, or scientific notions, I instead focus exclusively on sharing ideas and messages. The physical objects that enter into presentation are a byproduct. Presentations that I work on come from many discussions that take place with artists that engage with me. All processes are organic and take place because like-minded individuals gravitate towards each other or find ways of creating a critical dialogue between individuals and artistic statements.

This is the core concept uniting the artists of “AGENCY: ON WHO’S TERMS?” as the challenging of viewing is added to each individual artists work beyond the original intent of the artist during creation. We all work together to build concept forming an ad-hoc collective without name in the formation of group identity yet retain individual ideas, agency and control over viewing. Consent remains at the center of this exhibition with conscious misuse of terminology and grammar as it suits artistic purpose. Each work is not related to the next yet impacts overall view forcing audience to determine outcome challenging each individuals sense of Agency as the viewer sets their own terms.

Participating Artists

EE Portal Collective (Elyse Portal & Emilio Portal)

3 ways of working with plants:

1. the physical / 2. the essential / 3. the ethereal

3 ways of working with plants by ee portal is about intimacy. Working with plants in a physical way creates a visceral, tactile relationship. Smell, colour, grain, texture, movement all emerge from shaving, carving and sculpting one layer to the next. Working with plants in an essential way pushes us to perceive the luminous vibrations of colour that emanate all around us in our local worlds. Working with plants in an ethereal way deepens our understanding and knowledge of the otherwise unknown and often ignored sentience of the plant peoples. All 3 of these ways of working and knowing plants are ancient, and point to a very different, yet accessible world in which our ancestors walked, lived and dreamed in. 3 wall-mounted works will illustrate these 3 ways of working with plants: the physical, the essential & the ethereal.

Artist statement: At the root of our practice, we acknowledge the primordial essence of land and place. The epic, unspoken and tragic stories of nature have become our main source material. We are deeply interested in the idea that land is sentient, that it has emotions, and that the land itself is an artist. In our view, the land’s emotions are intrinsic to our own emotions. The land is the artist and we are the work. An important on-going discussion for us is the schism between natural manifestations versus human alterations. Human modification to the environment, on a large-scale, is never done by one individual. The larger destruction is agreed upon, albeit passively, by society as a whole. We challenge this passivity and unspoken agreement through our commitment to deeply questioning and re-investigating our age-old relationship, or lack thereof, with nature.

Raven Davis is an Indigenous, mixed race, 2-Spirit multidisciplinary artist, curator and activist from the Anishinaabek (Ojibwa) Nation in Manitoba. Born and raised in Tkaronto (Toronto) and currently splitting time working between K’jipuktuk (Halifax) and Tkaronto. Raven blends narratives of colonization, race, gender, erotica, their 2-Spirit identity and the Anishinaabemowin language and culture into a variety of contemporary art forms. Raven is also a proud parent to 3 sons. Highlighted in Canadian Art, Must Sees, Raven has been interviewed by No More Potlucks the CBC and the Huffington Post, and has been published in Canadian Art Magazine, Black Girl Dangerous, Plentitude Magazine and The Coast News Paper. Over the past 3 years, Raven has accomplished a nomination for the Sobey’s Art Award, has exhibited their artwork in part of the collateral events of the 2015 Venice Biennale and was the first art and activism, artist in residence for the Nova Scotia Art and Design University in 2016. Their films have made there way to international film festivals in Berlin, Amsterdam, New York City, Montreal and Toronto. Prior to that, Raven has worked as an independent designer and has volunteered on many boards that support the growth of art and cultural awareness.

Jessie Short is a curator, writer, and multi-disciplinary artist and emerging filmmaker whose work involves memory, multi-faceted existence, Métis history and visual culture. Short obtained an MA degree in 2011 and an Undergraduate degree in 2006, and has also received grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts council for her curatorial and film making practice. Short worked in the visual arts department at The Banff Centre for the Arts, and she also spent two years as the executive director of the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective in Toronto, Ontario. She is currently working on various contracts as a curator and documentary filmmaker.

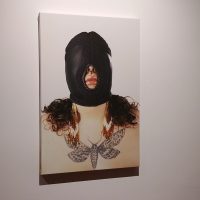

Dayna Danger is a 2Spirit/Queer, Metis/Saulteaux/Polish visual artist raised in so called Winnipeg, MB. Using photography, sculpture, performance and video, Dayna Danger‘s practice questions the line between empowerment and objectification by claiming space with her larger than life scale work. Danger’s current use of BDSM and beading leather fetish masks explores the complicated dynamics of sexuality, gender, and power in a consensual and feminist manner. Danger is currently based in Tio’tia:ke.

My Own Contribution: Clayton Windatt